We were eager to reexamine staging principles, delivery of text , voice and movement in the Renaissance model, which I am happy to say has caught on. All over the US and Europe the example set by the reconstructed Globe Theater in London is redefining performance techniques. The RSC has even redesigned its main stage to reflect this new sensibility. In regional theaters all over America actors are looking their audience in the eye and asking "Who calls me villain?" The feedback ASC has received since we started has as few common themes, among them: humor (even tragedies have light moments) and accessibility. Which brings me to Panto.

Shortly after drama school I was working as an actor in London when an actress with whom I shared an agent got a job in a Christmas Panto near my apartment. Now, the term "panto" was rarely uttered by any of my British colleagues, I observed, with out a roll of the eyes or at least an ironic tone, much as many New York actors react to the idea of soap operas. Well, I had seen my great-grandmother's favorite soap before I was old enough to object and knew such a popular genre was not popular for nothing. I therefore took the opportunity to see Dick Whittington, my first panto, and broaden my horizons a bit. What a treat! The production was a flood of stimulation - none of it accidental: Sarah the Cook (played by a man) threw candy to the kids, led a sing-along and shot sexual innuendoes and double entendres in every direction. The audience had a shouting match with King Rat (during his soliloquy) and was encouraged to shout advice to Dick Whittington's (sexy) cat, played by my actress friend. There were dresses, fights, jokes and romance in abundance and, having enjoyed a cup or two of wine during the performance, I left in a real "holiday" mood.

A little research into the origin of the modern Christmas Panto suggested its roots were in commedia dell'arte and had traveled to Britain from Italy in the 16th century. Another Renaissance form of entertainment, which worked wonderfully well today.

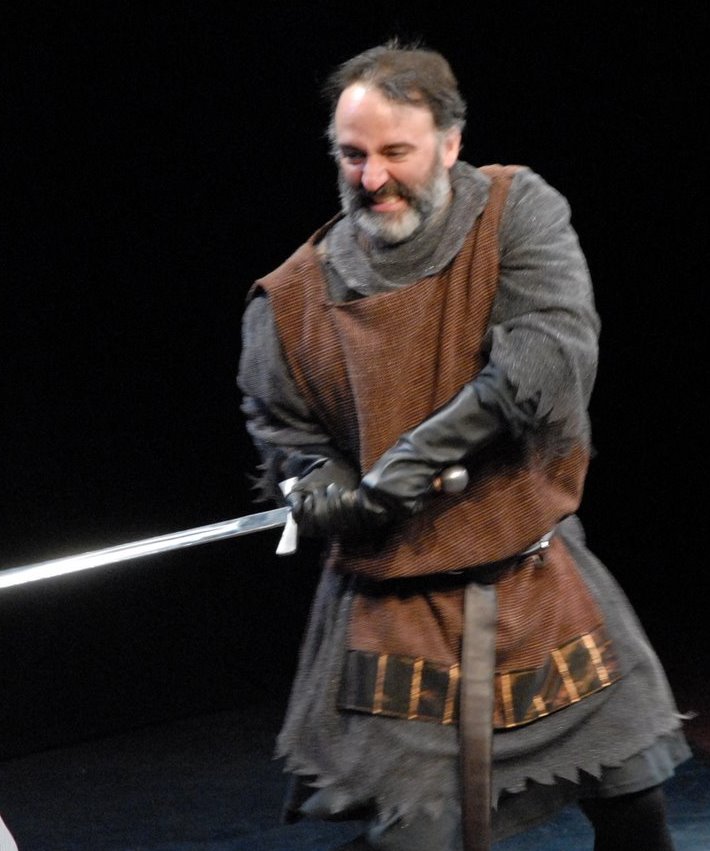

Panto is now considered family theater, but very different in my view from theater merely intended for consumption by young people. It was after seeing a particularly thin "young people's" dramatization of The Three Musketeers that I decided to pick up the book. My reading confirmed that the book didn't belong just in the juvenile section of the library, but as many great works of fiction, it had appeal across the generations. I had seen a few film versions and it was clear from the variety of popular interpretations, that the novel was a rich vein from which many different elements could be mined. There was of course action - lots of sword fighting, which I always loved - so it had appeal for boys. There was sex - which everybody likes... pretty much. Period dresses were, I had observed, very popular with girls. Throw in a bare chest or two, some of Dumas' clever repartee and as well as some of the book's tasty romance and you've got a family show. I therefore set about writing a new stage adaptation of the novel.

As I waded though French and English versions of the text, I began to see more than just a series of pleasant sensations for the reader. Without attempting to adapt Artaud's Theatre of Cruelty, I will simply suggest that we all to the theater or the movies for stimulation - of all kinds. This stimulation: emotional, intellectual or sensual can include revulsion, embarrassment and anger. Thus the uncooked fish I got to be brought out by the fishmonger in the London scene. We like pleasing images, noble actions and words and happy or funny outcomes of course, but we do like to be reviled a little as well I think. The fish, though far from a graphic image of gore or depiction of extreme emotional cruelty was meant to add a touch of bitter to an otherwise rich dish. On balance, I believe now my script could use a few more pinches of that kind of seasoning, especially if the Parisian baker and London apple seller had been able to distribute their wares to the audience as was intended. No eating or drinking allowed in the theater seats, alas. The actor who plays the fishmonger opted for a stuffed catfish toy rather than my frozen dorade in the end as well. Put off by the smell, alas. Alas.

Timur Kocak